SIBO vs SIFO: Diagnosis, Testing & Treatment Guide

SIBO vs SIFO: The Overlooked Difference Keeping You Bloated

Chronic bloating, gas, and fatigue can be stubborn and demoralizing. You may have been told it is SIBO and put on antibiotics, only to see symptoms return again and again. If that sounds familiar, you are not alone. There is an important piece of the puzzle that is often overlooked: fungal overgrowth of the small intestine, commonly called SIFO. SIFO can mimic SIBO almost symptom for symptom, but the causes, laboratory clues, and treatments can be different enough that missing it leads to relapses and prolonged suffering.

This article will walk you step by step through what SIBO and SIFO are, how they overlap, where they differ, how to test for them intelligently, and how to design an effective, practical plan that addresses root causes rather than only suppressing symptoms. The tone here is practical and clinical, but written for people who want clear action and explanation. I will cover diagnostic issues, why many tests fail to detect the real driver, pharmaceutical and botanical options, the role of biofilms, the unique biology of fungal organisms, and a stepwise clinical approach you can discuss with your practitioner.

Outline

What are SIBO and SIFO?

Key organisms involved

Risk factors that set the stage

How common are each of these problems?

Why symptoms alone usually cannot tell the difference

Diagnostic tools: strengths and limitations

Treatment options: pharmaceuticals, botanicals, probiotics

Biofilms and why they matter

The unique biology of fungus and why it can be elusive

A practical stepwise clinical approach: Clear, Correct, Protect

When to suspect SIFO and when to test for other drivers like H pylori

Lifestyle, nutrition, motility, and immune support

Sample clinical scenarios and sequencing

Key takeaways and next steps

What are SIBO and SIFO?

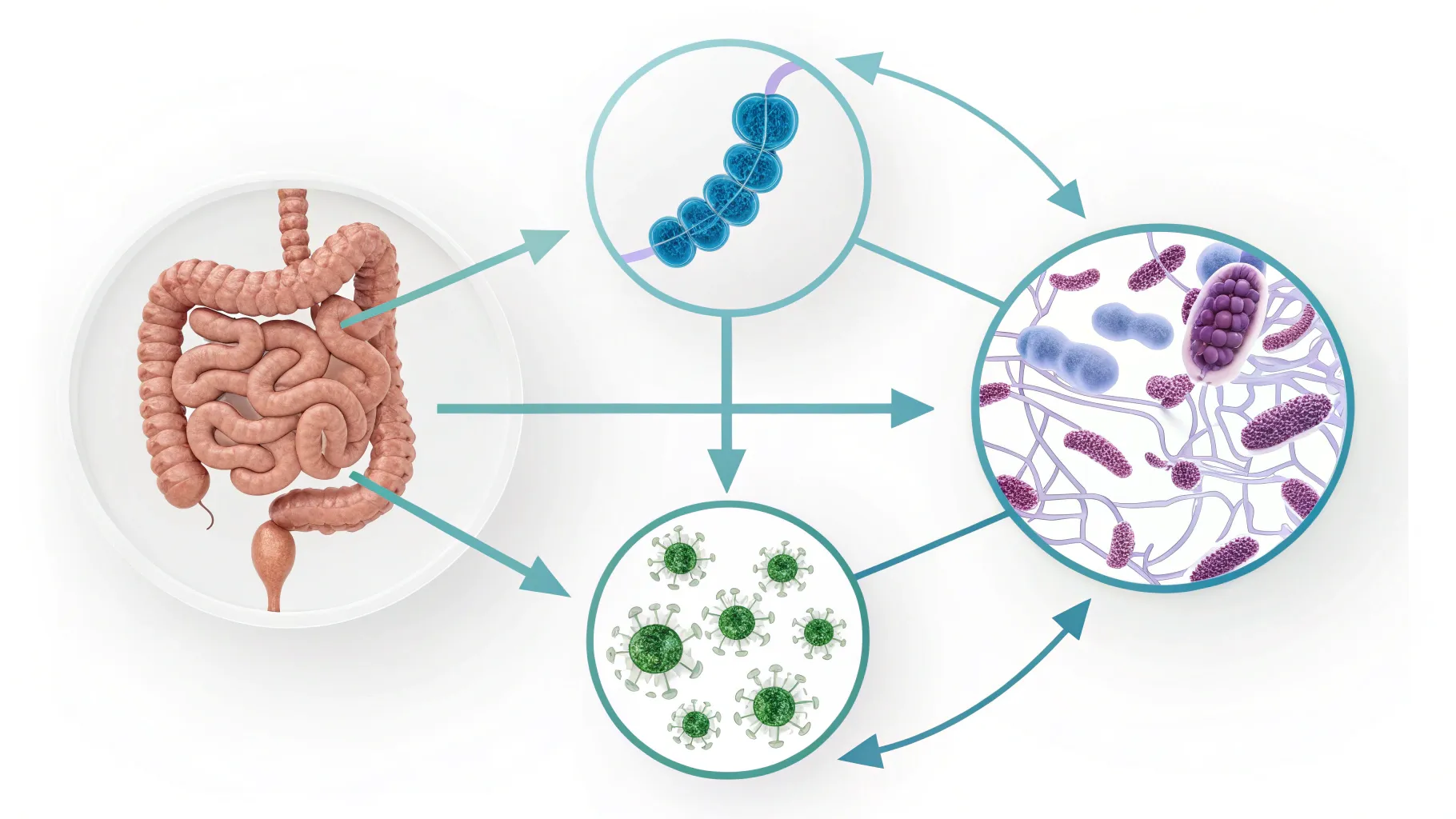

SIBO stands for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. It is a condition in which bacteria that normally live in the colon or external environment overgrow in the small intestine. The small intestine should have relatively low bacterial numbers compared with the colon. Excess bacteria in the small bowel can ferment carbohydrates, alter digestive secretions, interfere with absorption, and trigger symptoms like bloating, gas, diarrhea, constipation, and fatigue.

SIFO stands for small intestinal fungal overgrowth. This is conceptually similar to SIBO but driven by fungal organisms rather than bacteria. The most commonly implicated species are Candida, especially Candida albicans, but other Candida species and fungi can be involved as well. Like SIBO, SIFO can produce bloating, gas, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and systemic complaints. SIFO can also degrade the integrity of the gut lining, release virulence enzymes, and form biofilms that protect fungi and bacteria from treatment.

Key organisms involved

Understanding which organisms are commonly involved helps explain differences in biology and treatment:

SIBO - bacterial species commonly implicated

Escherichia coli (E. coli)

Klebsiella species

Streptococcus species

Other gram negative and gram positive gut bacteria

SIFO - fungal species commonly implicated

Candida albicans (most commonly implicated)

Other Candida species

Less commonly, other yeast or mold species

Some patients will have both SIBO and SIFO concurrently. This co-occurrence can complicate diagnosis and make single-modality treatment less effective.

Risk factors that set the stage

The conditions that allow microbial overgrowth in the small intestine are largely the same culprits that reduce the small bowel's ability to keep microbial numbers in check. These include:

Low stomach acid - Acid is an important barrier to microbial entry from the mouth and upper GI tract. Low acid allows survival and transit of bacteria and fungi into the small bowel.

Low bile and pancreatic enzymes - These digestive secretions both aid digestion and help control microbes. Insufficient secretion can promote overgrowth.

slowed intestinal motility - If the migrating motor complex and normal propulsive activity are reduced, microbes have more opportunity to multiply in the small intestine.

anatomical or structural changes - surgical alterations, strictures, adhesions, or diverticula can create pockets where microbes accumulate.

aging - digestive secretions and motility often decline with age, increasing risk.

immune suppression - this is particularly important for SIFO. Individuals with immunosuppressive states such as advanced illnesses, steroid use, or certain chronic conditions are at higher risk for fungal overgrowth.

metabolic disease and malnutrition - diabetes and malnutrition impair immune function and mucosal defences, making fungal overgrowth more likely.

Note that these risk factors overlap. Many people who develop bacterial overgrowth also have problems with acidity, enzymes, motility, or gut anatomy. But immunosuppression, diabetes, and steroid use are particularly prominent as risk factors for fungal overgrowth.

How common are each of these problems?

SIBO is common, though exact prevalence estimates vary depending on the population and testing method used. SIBO is more frequently recognized because breath testing and clinical awareness are more widespread. Conditions associated with higher rates of SIBO include:

Irritable bowel syndrome

Inflammatory bowel disease

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic disease

Post surgical anatomy or structural disorders

SIFO is less commonly recognized and therefore may be underestimated. Importantly, fungal overgrowth can coexist with SIBO. In many patients who relapse after antibiotic therapy for SIBO, missing an underlying fungal component is a major reason for recurrence.

Symptoms and why they overlap so much

The clinical symptoms reported by patients with SIBO and SIFO overlap heavily. Common complaints include:

Bloating and abdominal distension

Gas and flatulence

Diarrhea

Constipation or alternating stool patterns

Abdominal pain and cramping

Fatigue and cognitive fog in some patients

Because both bacterial and fungal overgrowth can ferment carbohydrates, disrupt digestion, and provoke immune responses, the symptom profiles are quite similar. A few subtle differences are worth noting:

Malabsorption is often more prominent with bacterial overgrowth - Bacterial overgrowth can deconjugate bile acids and interfere with fat absorption and certain micronutrient absorption. If you have evidence of fat malabsorption or specific nutrient deficiencies, that raises the probability of a bacterial contribution.

Fungal overgrowth more often produces virulence enzyme effects and mucosal disruption - Fungi release enzymes and virulence factors that can damage the gut lining, promote inflammation, and enable biofilm formation. This can produce systemic inflammatory effects and make the condition more resilient.

In practice, symptoms alone rarely allow a confident distinction between SIBO and SIFO. That is why targeted testing and a thoughtful therapeutic sequence are essential.

Diagnostic tools: strengths and limitations

Diagnosing SIBO and SIFO is one of the most challenging parts of clinical care in this area. No single test is perfect. Understanding the strengths and limitations of each option helps guide smart clinical decision making.

Small intestine aspirate and culture

The traditional gold standard for diagnosing small intestinal overgrowth is aspiration of small bowel contents followed by culture and direct sampling. This test can directly identify bacteria or fungi in the small intestine. However, there are several major barriers:

It is invasive, requiring endoscopy and specialized laboratory handling.

It is often impractical for widespread clinical use.

Sampling location matters; microbes can be patchy, and a single aspiration may miss overgrowth elsewhere in the small bowel.

Because of these limitations, clinicians commonly rely on less invasive indirect tests.

Breath testing

Breath tests measure hydrogen, methane, and sometimes hydrogen sulphide gases produced when bacteria ferment carbohydrates. They are noninvasive and widely used for suspected SIBO. Strengths and limitations include:

They can suggest abnormal bacterial fermentation in the small bowel.

Sensitivity and specificity are imperfect; false negatives and false positives occur.

Breath testing does not detect fungal overgrowth. If the underlying issue is fungal, a breath test may be negative or misleading.

Breath tests cannot identify specific organisms or reveal the status of digestive secretions, mucosal immunity, bile, or pancreatic enzyme function.

Stool testing and functional assessment

Stool tests have value, but not necessarily for directly diagnosing SIBO or SIFO. Their best utility is to assess the state of digestive secretions and mucosal immune function. What stool testing can reveal includes:

Markers of bile acid status, enzyme activity, and inflammatory markers.

Patterns that point to underlying drivers - for example, low bile or enzyme markers that predispose to overgrowth.

While stool testing can show some elevations in organisms like Streptococcus or E. coli, stool results do not reliably reflect small intestinal microbial populations. Stool primarily represents the colon microbiome.

Therefore, stool testing is most useful to identify the underlying vulnerabilities (digestive secretion insufficiency, immune dysfunction, inflammation) rather than as a definitive test for SIBO or SIFO.

Nutrient testing and markers of malabsorption

If bacterial overgrowth has been present for some time, nutrient deficiencies are common. Testing levels of key nutrients can be revealing:

Fat soluble vitamins and evidence of fat malabsorption

Vitamin B12 and other micronutrients

Tests for signs of systemic inflammation or immune dysfunction

Finding nutrient depletion consistent with malabsorption increases the likelihood that bacterial overgrowth is a significant contributor.

Putting all the information together for diagnosis

No single test reliably distinguishes SIBO from SIFO in all patients. Instead, a combination of clinical pattern recognition, breath testing, stool functional testing, nutrient markers, and assessment of risk factors gives the best clinical picture. Key points to incorporate:

If a breath test is positive, bacterial overgrowth is likely present. But if symptoms persist after appropriate antibacterial treatment, consider fungal overgrowth or biofilm persistence.

If the breath test is negative but symptoms strongly suggest microbial overgrowth and you have risk factors for fungal disease, suspect SIFO.

Assess immune function, digestive secretions, and motility. These are the root causes that must be fixed for durable response.

Treatment options: pharmaceuticals, botanicals, and probiotics

Treatment must be tailored to the specific organism(s) implicated and to the underlying drivers that allowed overgrowth to occur. Treatments fall into several categories: pharmaceutical antimicrobials, botanical or herbal antimicrobials, probiotics, dietary strategies, and lifestyle measures that improve motility, digestion, and immune function.

Pharmaceutical antimicrobials

When bacteria are the dominant driver, several antibiotics are commonly used:

Rifaximin - a nonabsorbable rifamycin antibiotic that concentrates in the gut and is widely considered a first-line pharmaceutical for non-constipation bacterial SIBO.

Metronidazole and neomycin - used in certain SIBO subtypes or in combination, depending on breath test results and clinical context.

For fungal overgrowth, pharmaceutical antifungals are generally from the azole class:

Fluconazole is an oral azole antifungal commonly used against Candida species. There are other systemic antifungals as wel,l depending on the organism and clinical scenario.

Important clinical point: Pharmaceutical antibiotics and antifungals are different classes of drugs that target fundamentally different organisms. If a patient responds to antibiotics and then relapses, the relapse may be due to remaining fungal overgrowth that was not addressed by antibiotics. Staging treatment or using combinations may be necessary, and failing to recognize the need for antifungal therapy is a common reason for persistent symptoms.

Botanical and herbal antimicrobials

Herbal and botanical antimicrobial blends often contain a mixture of compounds with antibacterial and antifungal activity. Examples include oregano oil, olive leaf, berberine-containing herbs, and others. Several practical points are important:

Botanical blends can have broad activity against both bacteria and fungi, which means a single botanical regimen can sometimes treat mixed SIBO-SIFO without needing two separate pharmaceutical classes.

Some data indicate that certain botanical antimicrobial blends are at least as effective as pharmaceutical treatments in some settings, particularly when treatment sequencing and duration are optimized.

Botanicals often have multiple mechanisms of action and lower systemic absorption, but they still require careful selection and monitoring for side effects and interactions.

One advantage of botanical therapy is the ability to use multiple agents with different mechanisms of action at the same time. This is particularly helpful against fungal organisms that can change form and evade single-mechanism treatments.

Probiotics

Probiotics can be a useful adjunct, but not all probiotics are equally helpful for SIBO or SIFO. A few points to consider:

Saccharomyces boulardii is a probiotic yeast with evidence for benefit in small intestinal microbial disorders. It appears to be helpful across bacterial and fungal overgrowth contexts, likely because it has anti-pathogen properties and can support mucosal immune responses.

Other probiotics may help in certain cases but can sometimes worsen symptoms for some individuals with small bowel overgrowth, so they must be chosen carefully.

Probiotics can be helpful during and after antimicrobial therapy to support mucosal recovery and to help crowd out pathogenic microbes when used appropriately.

Dietary strategies

Diet is often discussed in the context of SIBO, and several dietary approaches are promoted. Two important clarifying notes:

The low FODMAP diet is an effective strategy for many patients with irritable bowel syndrome because it reduces fermentable carbohydrates that feed bacterial fermentation. However, it is not the same as a targeted SIBO diet and can have downsides when used long term, especially if the goal is to restore normal microbiome function.

For both SIBO and SIFO, dietary modifications can reduce symptoms and make antimicrobial therapies more effective, but diet alone is rarely sufficient if underlying motility, secretions, or immune issues are unaddressed.

In practice, a short-term reduction of highly fermentable carbohydrates can reduce symptoms during active antimicrobial therapy, while longer-term strategies should aim to restore normal diet variety and gut function once the overgrowth has been cleared and the mucosa has healed.

Biofilms: the microbial shield that creates relapses

Biofilms are communities of microbes encased in a protective extracellular matrix. Both bacteria and fungi can form biofilms. Biofilms matter for three reasons:

They protect microbes from antimicrobial agents and immune attack.

They allow microbes to persist and then shed, causing recurrent symptoms.

They increase the difficulty of fully eradicating an overgrowth with a single course of medication.

Breaking down biofilms is often essential for complete eradication. Several agents and strategies can help disrupt biofilms. Examples include certain botanicals such as oregano and olive leaf extracts, as well as some pharmaceutical agents that appear to have anti-biofilm properties. Additionally, enzymatic agents and specific biofilm disruptors are available in clinical practice. Carefully chosen combinations of antimicrobials and biofilm-disrupting agents are often the most effective approach.

The unique biology of fungus: yeast form vs hyphal form

Fungal organisms exhibit a biological flexibility that bacteria generally do not. Candida and other fungal species can switch between different physical forms depending on their environment. Two clinically important forms are:

Yeast form - This form tends to be more mobile and is associated with colonization and spread throughout the GI tract.

Hyphal form - This filamentous form allows tissue penetration, mucosal invasion, and stronger inflammatory responses. The hyphal form is associated with virulence and mucosal damage.

This ability to change form, also called phenotypic plasticity, makes fungal infections more dynamic and sometimes more difficult to eradicate. One strategy to address this is to use multiple antifungal agents with different mechanisms of action simultaneously or sequentially. Botanicals that act on different fungal targets are particularly useful because they can blunt multiple virulence mechanisms at once.

Clinical sequencing: Clear, Correct, Protect

Treating SIBO and SIFO effectively often requires a staged approach. A simple clinical framework that works well in practice is:

Clear - Eradicate the microbial overgrowth, including addressing biofilms. This may involve antibiotics, antifungals, in combination with botanicals and biofilm disruptors.

Correct - Fix the underlying drivers that allowed overgrowth to occur. This includes improving stomach acid, bile, pancreatic enzymes, motility, and correcting nutrient deficiencies.

Protect - Rebuild the gut ecosystem and barrier, support immune function, use targeted probiotics, and implement lifestyle changes to prevent recurrence.

Sequence matters. For example, if H pylori is present, it can influence upper GI physiology and should often be treated in the correct order relative to SIBO or SIFO. Similarly, clearing an overgrowth without correcting motility and digestive secretions leads to relapse. Each phase has its own interventions and monitoring strategies which I will outline below.

Clear phase: targeted eradication

During the Clear phase, the goal is to remove the bulk of the pathogen load and disrupt biofilms. Clinical options include:

Pharmaceutical approach - Use antibiotics for SIBO or antifungals for SIFO based on testing and clinical cues. Sometimes combination therapy is necessary for mixed infection.

Botanical approach - Use evidence-based antimicrobial botanicals that span antibacterial and antifungal activity. Blended botanical therapies often reduce the need for two separate pharmaceutical classes because they have broad spectrum activity.

Biofilm disruption - Use agents known to interrupt biofilm matrices. This may include olive leaf, oregano, N-acetylcysteine in certain protocols, or other enzymatic therapies. The right combination of antimicrobials and biofilm disruptors helps avoid relapses.

Duration of therapy varies with severity, organism, and response. Close clinical monitoring is essential.

Correct phase: addressing the drivers

After the pathogen burden is reduced, correcting the underlying drivers is essential for long term remission. Focus areas include:

Motility - Improve the migrating motor complex and correct delayed gastric emptying or small bowel motility problems. Prokinetic agents and lifestyle strategies such as postprandial walking and avoiding snacking are useful.

Stomach acid and digestive enzymes - Where low acid or low pancreatic enzymes are suspected, targeted replacement under clinician supervision can improve digestion and barrier function.

Bile support - If bile acid testing suggests deficiency or malabsorption, bile acid support may be indicated, or investigate causes of bile insufficiency.

Immune function - Assess for immunosuppression, treat reversible causes, and support mucosal immune health with targeted nutrients and strategies.

Nutrient repletion - Correct vitamin and mineral deficiencies identified in testing, as these support mucosal healing and immune competence.

Protect phase: rebuild and prevent

In the Protect phase, the focus is on restoring a healthy microbiome, preventing re-seeding, and maintaining physiological resilience. Strategies include:

Targeted probiotics - Use strains with evidence for benefit, including Saccharomyces boulardii. Consider prebiotic strategies once symptoms are controlled.

Dietary diversity - Gradually reintroduce a varied diet to support a resilient microbiome, while monitoring symptoms.

Lifestyle and stress management - Sleep, stress reduction, and regular exercise support immune and motility functions.

Maintenance regimens - In some individuals with recurrent disease, periodic pulses of antimicrobials or botanicals combined with biofilm support and ongoing motility therapy prevent relapse.

When to suspect SIFO

Consider SIFO when:

Symptoms persist after adequate antibacterial therapy for SIBO.

Breath testing is negative but clinical symptoms suggest ongoing microbial overgrowth and there are risk factors for fungal disease (e.g., diabetes, steroid use, immunosuppression).

There are signs of mucosal disruption or inflammatory markers that suggest fungal virulence factors are present.

Stool or small bowel aspirate (if performed) identifies Candida species or other fungi.

In these settings, adding antifungal therapy or broad-spectrum botanicals that include antifungal agents is reasonable, especially when combined with biofilm disruptors and root cause work.

H pylori and the upper gut: why this matters

H pylori infection is common and can profoundly impact upper GI physiology, including acid secretion and motility. It can change the way SIBO behaves and may need to be addressed in a particular order relative to SIBO or SIFO therapy. If H pylori is present, treating it in the right sequence and managing the downstream effects on acid and motility often improves outcomes for small intestinal overgrowth as well. Make sure H pylori is considered and tested for when upper gut dysfunction is part of the clinical picture.

Practical testing algorithm to discuss with your clinician

Below is a suggested stepwise approach to testing and management. This is a general framework and should be individualized by a qualified clinician.

Clinical assessment and history

Document symptoms, dietary patterns, medication use (including acid blockers and antibiotics), surgical history, and risk factors for immune suppression.

Initial noninvasive testing

Breath test to assess for bacterial fermentation (hydrogen, methane, hydrogen sulfide when available).

Comprehensive stool functional testing to assess digestive secretions (bile, enzymes), inflammation, and microbial patterns that suggest underlying drivers.

Nutrient testing for markers of malabsorption.

Interpretation

Positive breath test suggests SIBO. Negative breath test with strong symptoms and risk factors for fungal disease suggests SIFO might be present.

Stool results pointing to low bile, low enzymes, or reduced mucosal immunity indicate correction needs to be part of the plan.

Clear phase therapy

Choose antibiotics or botanicals based on testing, clinical context, and patient preference. For suspected fungal disease, include antifungal agents or botanicals with antifungal activity. Use biofilm disruptors when indicated.

Correct phase interventions

Address motility, digestive secretions, nutrient deficiencies, and immunological drivers identified in testing.

Protect phase

Repopulate with targeted probiotics, restore dietary diversity, and implement lifestyle changes.

Reassess

Monitor symptoms and repeat testing selectively if symptoms recur. Consider small bowel aspirate in complex or refractory cases if feasible.

Sample clinical scenarios

Scenario 1 - Classic SIBO response then relapse

A patient with bloating and diarrhea tests positive for hydrogen on a breath test. They are treated with rifaximin and experience improvement, but within months symptoms return. What to consider:

Relapse may result from not correcting motility or digestive secretions. Address the migrating motor complex and enzyme/bile status during the Correct phase.

Consider coexisting SIFO. If fungal overgrowth was unrecognized, add antifungal therapy or botanical antifungals and biofilm disruptors.

Evaluate biofilms as a reason for persistence and incorporate specific anti-biofilm agents.

Scenario 2 - Breath test negative but persistent symptoms

A patient has negative breath testing but ongoing bloating and abdominal pain. They have a history of long term steroid use. What to consider:

Steroid use increases the risk of fungal overgrowth. SIFO should be suspected even with a negative breath test because breath testing does not detect fungi.

Stool functional testing focusing on mucosal immune markers and fungal PCR, if available, can help. Consider adding antifungal botanicals or pharmaceuticals as clinically appropriate.

Assess immune competence and correct reversible causes.

Scenario 3 - Mixed infection

A patient has some positive breath test results and stool evidence of Candida overgrowth. What to consider:

Mixed SIBO-SIFO is common and requires treating both bacterial and fungal components.

Botanical blends with both antibacterial and antifungal activity plus biofilm disruptors can be advantageous because they treat multiple targets simultaneously.

Follow Clear, Correct, Protect sequence and ensure motility and digestive secretions are optimized before stopping therapy prematurely.

Lifestyle and nutrition: the often underestimated pillars

Medications and botanicals are only part of the solution. Long term success requires restoring physiologic resilience. Key lifestyle measures include:

Sleep - consistent restorative sleep supports immune function and gut healing.

Stress management - chronic stress impairs motility and immune responses. Practices such as meditation, breath work, psychotherapy, or mindfulness are helpful.

Regular physical activity - exercise stimulates motility and supports metabolic health.

Meal timing - avoid frequent snacking which disrupts the migrating motor complex. Allow longer fasting windows between meals to support natural cleansing waves.

Targeted nutrition - support mucosal healing with adequate protein, essential fatty acids, and micronutrients identified as deficient in testing.

Common questions and practical answers

Can botanicals replace pharmaceuticals?

Botanicals can be very effective and in many cases are a practical first line or adjunctive option. They often have broad activity against both bacteria and fungi and can be particularly useful for patients who prefer nonpharmaceutical approaches. However, severe or invasive infections, or certain patient-specific circumstances, may require pharmaceutical therapy. The choice should be individualized.

Should I be worried about taking antifungals if I do not have a confirmed fungal test?

Empiric antifungal therapy is a clinical decision based on symptom patterns, risk factors, and response to previous therapy. If you have risk factors for fungal disease and symptoms persist after antibacterial therapy, a trial of antifungal therapy under clinician supervision is reasonable. It is better to base therapy on testing when possible, but remember that testing options have limits.

How long should treatment last?

Treatment duration depends on severity, organism, and response. Short courses may work for some patients, but many require multiweek or multi-month strategies, especially when biofilms are involved. The Clear, Correct, Protect framework emphasizes clearing the infection, correcting root causes, then protecting and rebuilding. Do not stop corrective or protective measures prematurely.

Can SIFO occur in healthy people?

Yes. While immunosuppression and metabolic disease increase risk, SIFO can also occur in otherwise healthy individuals when local gut defenses are impaired, motility is slow, or after repeated antibiotic exposure that disrupts the normal microbiome balance.

Key takeaways

SIBO and SIFO can look almost identical symptomatically, which is why missing the fungal component is a common cause of relapse after SIBO treatment.

Breath testing detects bacterial fermentation but does not detect fungal overgrowth. A negative breath test does not rule out SIFO.

Stool functional testing is most valuable for assessing digestive secretions, bile, pancreatic enzyme function, and mucosal immune status rather than for direct small intestinal diagnosis.

Pharmaceutical antibiotics and antifungals are distinct drug classes that target different organisms. Missing a fungal contributor means an antibiotic alone will often be insufficient.

Botanical antimicrobial blends can have activity against both bacteria and fungi and often include biofilm-disrupting activity, making them a useful option for mixed or uncertain infections.

Fungal organisms can shift between yeast and hyphal forms, complicating eradication. Multiple mechanisms of action are often necessary to overcome fungal phenotypic plasticity.

Addressing root causes - motility, acid, bile, enzymes, immunity, and nutrition - is critical for durable recovery. Clear, Correct, Protect is an effective clinical framework.

Always evaluate for H pylori and other upper GI drivers when upper gut dysfunction is present, and treat in the correct sequence to improve outcomes.

Next steps if you are struggling

If you have chronic bloating, gas, or fatigue that relapses after standard SIBO therapy, consider the following action items to discuss with your clinician:

Re-evaluate testing. Consider stool functional testing and nutrient testing to identify drivers like low bile, low enzymes, or malabsorption.

Consider whether fungal overgrowth could be present, especially with risk factors like steroid use, diabetes, or immune compromise.

Ask about biofilm assessment and use of biofilm-disrupting agents as part of your eradication strategy.

Work with your clinician to design a Clear, Correct, Protect plan that includes mobility support, digestive secretion optimization, nutrient repletion, and appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Incorporate targeted probiotics such as Saccharomyces boulardii during the Protect phase.

Address lifestyle factors: sleep, stress, exercise, and meal timing to support motility and immune function.

Final thoughts

When SIBO symptoms keep returning and a single course of antibiotics does not deliver lasting relief, it is tempting to assume treatment failure or patient noncompliance. More often than not, the clinical picture is incomplete. Fungal overgrowth and biofilm persistence are common, under-recognized contributors that require a different set of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Understanding the differences and overlaps between SIBO and SIFO empowers you and your clinician to build a comprehensive plan that eliminates the overgrowth, repairs the gut, and prevents relapse.

Take a stepwise approach: clear the overgrowth, correct the root physiological problems, and protect the gut ecosystem. With a thoughtful strategy that addresses all three phases, most patients achieve meaningful and lasting improvement.

If you are struggling with recurrent bloating after SIBO treatment, do not assume bacteria are the only problem. Consider fungal overgrowth, assess biofilms, and treat in a sequence that fixes the root causes. Durable recovery requires more than a single antibiotic course.